Afghanistan: Settling In (2)

A memoir of life in Kabul, Afghanistan from 1976 to 1978: Part II

In the 1960s, after decades of being referred to as a hermit nation, Afghanistan opened its doors fully to the international community. The 1960s brought diplomats, international assistance experts, scholars, journalists, archaeologists, engineers, business people and adventurers to Afghanistan.

It also brought Peace Corps Volunteers. American President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 10924 establishing the Peace Corps on March 1, 1961. By June 30, 1962, 2,816 volunteers were serving two-year stints in 37 countries, including Afghanistan.

The 1960s were a time of major construction projects. The Russians built Kabul Airport in 1960. The Americans, working with Afghan engineers, designed and asphalted the major highway from Herat (near the western border with Iran) to Kandahar (in the south) and from Kandahar to Kabul.

The Russians designed and built the highway from Mazar-i-Sharif (in the north) to Kabul. They also built the Salang Tunnel, a major north-south connection in Afghanistan. The tunnel, completed in 1964, is nearly 3,200 meters (10,500 feet) above sea level and 2.67 kilometers (1.66 miles) long.

Kabul

Kabul is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. In 1976, it had a population of about 730,000 people. (In 2023 it has a population of 5 million!) The city is located in a narrow valley in the Hindu Kush Mountains. At an elevation of 1,790 meters (5,873 feet), it is one of the highest capital cities in the world.

Kabul is believed to be over 3,500 years old. Although it has been destroyed numerous times throughout its existence (for example, by Genghis Khan and his Mongol warriors in the 13th century and by the British in the 19th century), it has revived each time. It was also a key way station on the ancient Silk Road, which was a network of trade routes through which goods, culture, religions and technologies flowed between China and Europe from the second century BCE to the 8th century CE.

In 1969, Kabul’s first luxury hotel, the Intercontinental, arrived. It was located on a mountaintop to the east of the central core and had beautiful views of the city below it. The Intercon had a bar, two dining rooms, a bookstore, elevators and a swimming pool. Rock bands frequently performed in the dining room on the upper level, encouraging visitors to dance late into the night.

In February 1968, the Beatles embarked on their famous journey to Rishikesh, India to study Transcendental Meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. This awakened the desire in Baby Boomers from Europe, the U.S., Canada and beyond to visit India. Many sought spiritual enlightenment. Others sought adventure. Still others sought business opportunities.

Whatever their motivations, thousands of young people headed overland from Europe to India, and many of them went through Afghanistan. This hippy trail, almost like a contemporary Silk Road, resulted in an exchange of cultures, customs and products. After accomplishing whatever they had set out to do in India, many of these young people returned to Kabul to live for a while, attracted by the ease of living and the world’s best hashish.

This was the milieu into which I entered in 1976.

Moving in with Alcy

After completing the two-month Peace Corps training, I moved into a house with another volunteer named Alcy, who had already been in the country for several months. Alcy was from Delaware, and she was strong, intelligent and passionate about making a difference.

Our house was located in an area of the city called Shahr-i-Nau. Shahr means city and nau means new in Dari, but this is a misnomer because the district was one of the older ones in Kabul. Houses here were built in the traditional way, with either one or two stories. They were always surrounded by high walls for privacy. Inside the walls were gardens filled with flowers, lawns and trees.

Our one-story house had two bedrooms, a basic kitchen, a living room and a bathroom. The bathroom had a shower, but the only way to heat water was by building a wood fire under the water tank. So most of the time, we simply took freezing cold showers.

The water in Afghanistan was not potable, so we had to boil it in order to drink it. Because bottled drinking water had not yet been invented(!), we could only drink hot tea or bottles of Pepsi or Fanta (an orange drink) when we were outside the house. I have always disliked soft drinks, so my drink of choice was tea. The word for tea in Afghanistan is simply chai. Wherever I went, I could choose either chai siyah (black tea) or chai sabz (green tea).

Even on a Peace Corps salary, we could afford a half-time servant, whom we shared with another Peace Corps household. As far as my experience goes, servants in foreign households were always male. Their salaries supported their families, and they provided a huge service to their employers by cooking meals, washing their clothes by hand, and keeping the house clean.

Since there were no western-style grocery stores in those days, people bought food in the bazaars, which necessitated going from the fruit and vegetable sellers to the spice seller to the chicken seller to the lamb seller, and so on. Having someone who could do this for us was a huge help.

When you think about it, it is kind of funny what memories remain with you from the past. They are not always hugely IMPORTANT. Sometimes they are just snippets of a scene.

For example, I remember that Alcy had a cassette player on which we used to listen to music. This is where I first grew to love Cat Stevens. I played Alcy’s cassette of Teaser and the Firecat again and again. Even now, 45 years later, whenever I hear songs from that album (especially How Can I Tell You, Morning Has Broken, Moonshadow and Peace Train), I am immediately transported back to Kabul and to the people I met there.

I also remember sitting one day on cushions on the floor in our living room. Alcy was there, as well as another Peace Corps Volunteer named Winna. (Winna and her husband Jim were the young married couple in my Peace Corps cohort.) We had gotten hold of a copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, and it was a revelation to us.

The ‘60s and ‘70s were clearly an era of transformation, not the least in how women viewed their bodies and their sexuality. This book, which was published in 1970, was the first to openly address such issues as sexual orientation, gender identity, birth control, abortion, pregnancy and menopause. It encouraged women to enjoy sex and engage in it actively rather than simply being a docile, passive bystander to their aggressive male partners.

That afternoon, we talked about how we felt about being women and how we felt about our bodies and sex. The scene was actually quite remarkable if you pull back from it and consider the culture we were in and how the freedom of the Afghan women all around us did not depend on their own agency but on the whims of the men who controlled their entire society.

Discovering the bazaar

Shortly after moving in with Alcy, I was in the Peace Corps compound when an experienced volunteer named Tom came up to me.

“Grab your camera, Clarice,” he said. “We’re going to the bazaar. You must take pictures now, when everything is new. In a few months, this will all seem normal, and you will forget how amazing it is.”

I did what I was told, and we set out to explore. Tom started by taking me to Chicken Street, which was popular among the hippies and international community for its fascinating mixture of shops, cheap hotels and restaurants.

I didn’t want to look like a tourist, and I didn’t want to offend anyone, so unfortunately the pictures I took that day are some of the few that I have. (Also unfortunately, they are inside a scrapbook that is in a storage space in Portland, Oregon. Since I am writing this in Ireland, it is impossible to share those photos here. I will attempt to describe what I saw and provide other people’s pictures when I can find them.)

What do my pictures illustrate?

Traditional narrow, one-room shops clustered together that opened at street level and specialized in just one commodity, such as wicker baskets, ceramics, and silver jewelry made from lapis lazuli and malachite. (At night the proprietors closed their shops with wooden shutters.)

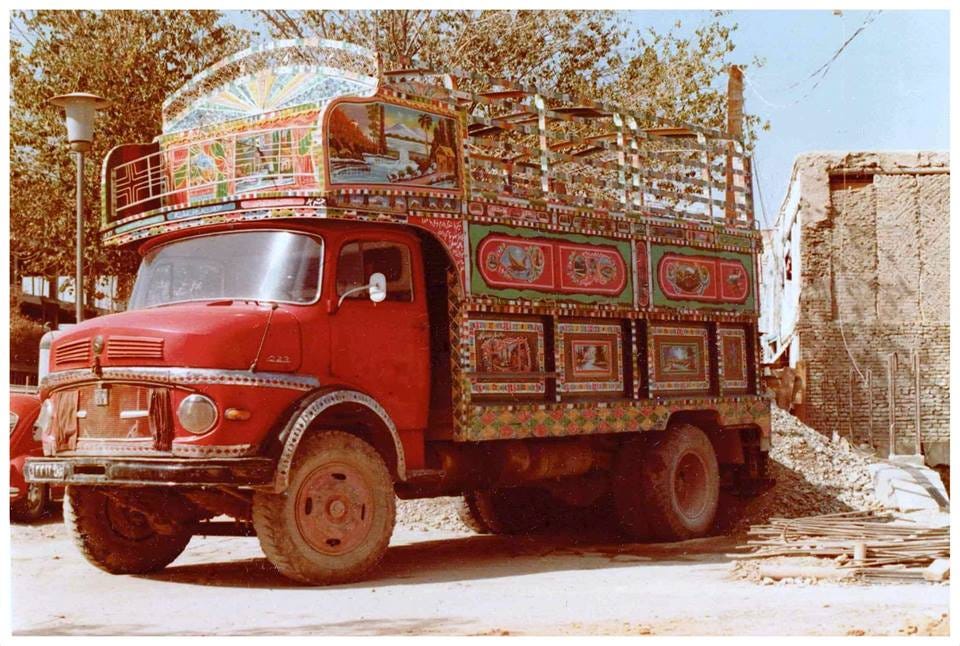

Streets filled with cars, bicycles, and carts pulled by donkeys. Intricately decorated, brilliantly painted trucks, each a unique work of art.

Women in western clothes, women wearing chadris, and school girls dressed in knee-length dresses with small white scarves draped around their shoulders. Nomadic Kuchi women, their faces proudly uncovered, wearing heavily embroidered, brilliantly colored dresses over loose-fitting leggings.

Bearded men wearing turbans and peran tumban (a loose shirt that falls below the knees that is worn over loose, baggy pants). Clean-shaven men wearing suit jackets over jeans. Two fierce looking men (they didn’t like having their picture taken!) with green and blue striped chapan coats draped over their shoulders.

Fruit stands overflowing with juicy, sweet pomegranates, melons, grapes and apricots. Dried fruit and nut stands piled high with raisins, dates, mulberries, pistachios and almonds. Vegetable stands bulging with vine ripened tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots and eggplants. Heaps of fresh spinach, mint and coriander. (People tend to either love or hate fresh coriander. I am in the love camp!)

Spice sellers sitting cross-legged on the ground, surrounded by mounds of fragrant cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, coriander, cumin and black pepper.

Bird cages for sale, as well as cages filled with all kinds of birds, including fighting Kawks (partridges), song birds, and exotic pigeons prized by people who flew pigeons for sport from their rooftops.

How we entertained ourselves

It’s hard to imagine now, but there was no internet in 1976, and computers and cell phones had not yet been invented. Nor did we have TVs. We did have telephones, but it was really expensive to make international calls. So when we communicated with families back home, we wrote letters. On one side of a thin piece of blue paper. After finishing the letter, you would fold the paper in thirds so that the blank outside was showing. This is where you wrote the address and pasted the stamps.

So how did we keep ourselves busy when we weren’t working at our jobs?

Books

For one, we read a lot of books. Although Amazon did not yet exist, it was possible (although expensive) to occasionally order books from abroad. People in the international community would gift their books to others when they left. Many books—in English and German and French—ended up in the hands of local booksellers, who would spread their wares out on the sidewalk.

In fact, I bought one of my favorite books ever from a sidewalk book seller in Kabul. It is a small, thin paperback called Music that was published in India in 1973. The author is Hazrat Inayat Khan, an amazing Indian musician and spiritual teacher who founded the Sufi Movement in the West. I love this little book so much that I brought it with me when I moved back to Seattle from Kabul, when I moved to Portland, Oregon, when I moved to Vienna, Austria, and when I moved to County Kerry, Ireland.

Parties

We socialized a lot with each other. With other Peace Corps Volunteers as well as with people in the international community. There were receptions, dances and special events at the Intercon as well as in various places around the city, and Peace Corps Volunteers were often invited.

The German Club

Afghan people in their homes were absolutely wonderful. But as a young foreign woman who walked the same streets every day to her teaching job, life could sometimes be difficult. Men would constantly call out and make remarks, and teenage boys would ride by on their bicycles, pinch my behind, and be gone before I could defend myself.

Therefore, the German Club was a wonderful haven, even if I went there only once in a while. Located in Shahr-i-Nau, it consisted of a large walled garden, a club house with a restaurant, a beautiful open-air swimming pool, and a bar that served alcoholic drinks. (Since Moslems are forbidden to drink alcohol, only facilities that catered to foreigners were allowed to serve it.) People from throughout the international community were welcome to visit the club—even Peace Corps Volunteers.

I remember sitting under a tree in the garden one afternoon while reading a book. I heard laughter and looked up to see two German women in miniscule bikinis climb into the swimming pool. The remarkable thing about this was that they were both around eight months pregnant. As someone from a still fundamentally Puritanical America, it was a revelation to me that women could be so comfortable with their bodies in public, even in the late stages of pregnancy. (I have no idea what the Afghan waiters thought!)

I happened to be reading a textbook on astrology that day. All of a sudden, a fat finger jabbed at my book, and I heard a voice say “that’s the devil!” In astonishment, I looked up and saw a fleshy, middle-aged man glaring down at me. I had no idea who he was or how to reply to him, so I just shrugged and tried to ignore him.

I learned later that he was a Jehovah’s Witness from Germany who was in Kabul to save people from their sins. It was completely illegal for him to try and convert Afghans, so he concentrated on Westerners instead.

Amateur theater

A major way that the international community kept busy was through theater. The British, in particular, were passionate about staging and acting in plays, but they welcomed other members of the English speaking community (including the Americans, Canadians, Australians and Dutch) into their productions as well.

I remember seeing two plays in particular that were professionally staged and acted. Both were by the English playwright Peter Shaffer. The first one, written in 1964, was The Royal Hunt of the Sun. It deals with the conquest of Peru by the Spaniards and has two main characters: Atahuallpa Inca and Francisco Pizzaro. The second one, written in 1973, was Equus. It tells the story of a young man who has a religious obsession with horses and the psychiatrist who tries to help him.

The reason I mention these is that they were so powerful—and so powerfully performed—that I still remember how emotionally drained I felt after watching them.

Buzkashi

The international community also occasionally attended Buzkashi matches in Kabul’s Ghazi Stadium. Sometimes referred to as “Afghan polo,” Buzkashi was the national sport of Afghanistan then, and it was not for the feint of heart.

The game originated among the nomadic Turkic peoples (Uzbek, Turkmen, Kazak and Kyrgyz) of Central Asia. The basic idea is simple. Men on horseback vie to pick up the carcass of a headless goat from the ground and ride it free and clear of all other riders. In the process, competitors do whatever they can to wrest the goat away. This includes kicking and whipping their opponents. (Although competitors are not allowed to pull other riders’ hair or their horses’ reins or to use weapons other than whips.)

As a result, the men wear heavy protective clothing. When they’re not using their whips, they carry them in their teeth to keep their hands free for racing their horses.

Buzkashi horses are highly trained and often worth thousands of dollars. (One owner I found online charges between $2,000 and $50,000 for his horses!) As a result, the horses are usually owned by wealthy men, not the riders themselves.

The game is at its fiercest in the north, around Mazar-i-Sharif, where it can go on for days and involve hundreds of men on horseback racing across the plains and rivers. In Ghazi Stadium in Kabul, however, Buzkashi was much more contained and even followed a few rules.

For example, the game consisted of two competing teams, each of which had 10 riders. Playing time was divided into two 45-minute periods, and the game was supervised by a referee. The teams vied to pick up the goat carcass, race to the end of the stadium, race back again, and drop the carcass in a chalk circle drawn on the field.

Even with such rules, the game was really exciting to watch. And the people in the stadium went wild when their favorite team was ahead!

Travel

On our days off, we sometimes traveled to different places in Afghanistan. For example, one weekend another Peace Corps Volunteer named Charlie and I decided to take a bus to Mazar-i-Sharif. Mazar is one of the largest and most ancient cities in Afghanistan, but it is particularly famous for the Shrine of Hazrat Ali, which is a spectacularly beautiful blue mosque.

The first mosque on the site was built in the 11th century by Sultan Ahmad Sanjar over the grave of a scholar and mystic named Ali ibn Abi Talib al-Balkhi. Genghis Khan completely destroyed the mosque in the 13th century when he massacred the entire population of the area and destroyed their places of worship.

The mosque was then rebuilt in the 15th century under the guidance of Sultan Husayn Bayqara. Over the centuries, it eventually fell into disrepair. It was restored again in the 1860s by Sher Ali Khan. This is when it was covered with the beautiful blue tiles that Charlie and I saw during our visit.

Non-Mulims are not allowed to go inside the mosque, but it was still worth the trip to see the amazing exterior.

The Buddhas of Bamyan

During the fall, I also visited Bamyan to see the Buddhas. That is what I will write about in my next post.

Music Recommendations

If you would like to experience music that is typical of Afghanistan, check out the two videos below.

Ahmad Zahir

Even though he died in 1979 at the age of 33, Ahmad Zahir is still considered to be Afghanistan’s greatest singer.

Homayoun Sakhi

One of Afghanistan’s most iconic instruments is the lute-like rubab, which is traditionally made from the trunk of a mulberry tree. Homayoun Sakhi (who now lives in the U.S.) is a master player.

Sooo many memories have been stimulated by your recollections. Did you ever hear Usted Malang who played the tabla. He was amazing....

What an amazing experience! I had no idea. The world has certainly changed in the short years since you were there and I am really enjoying learning more about how things used to be. Beautifully written!