Afghanistan: Bamiyan and the Buddhas (3)

A memoir of life in Kabul, Afghanistan from 1976 to 1978: Part III

During the two-month Peace Corps training that took place during the summer, Louis Dupree told us about a region west of Kabul called Bamiyan.

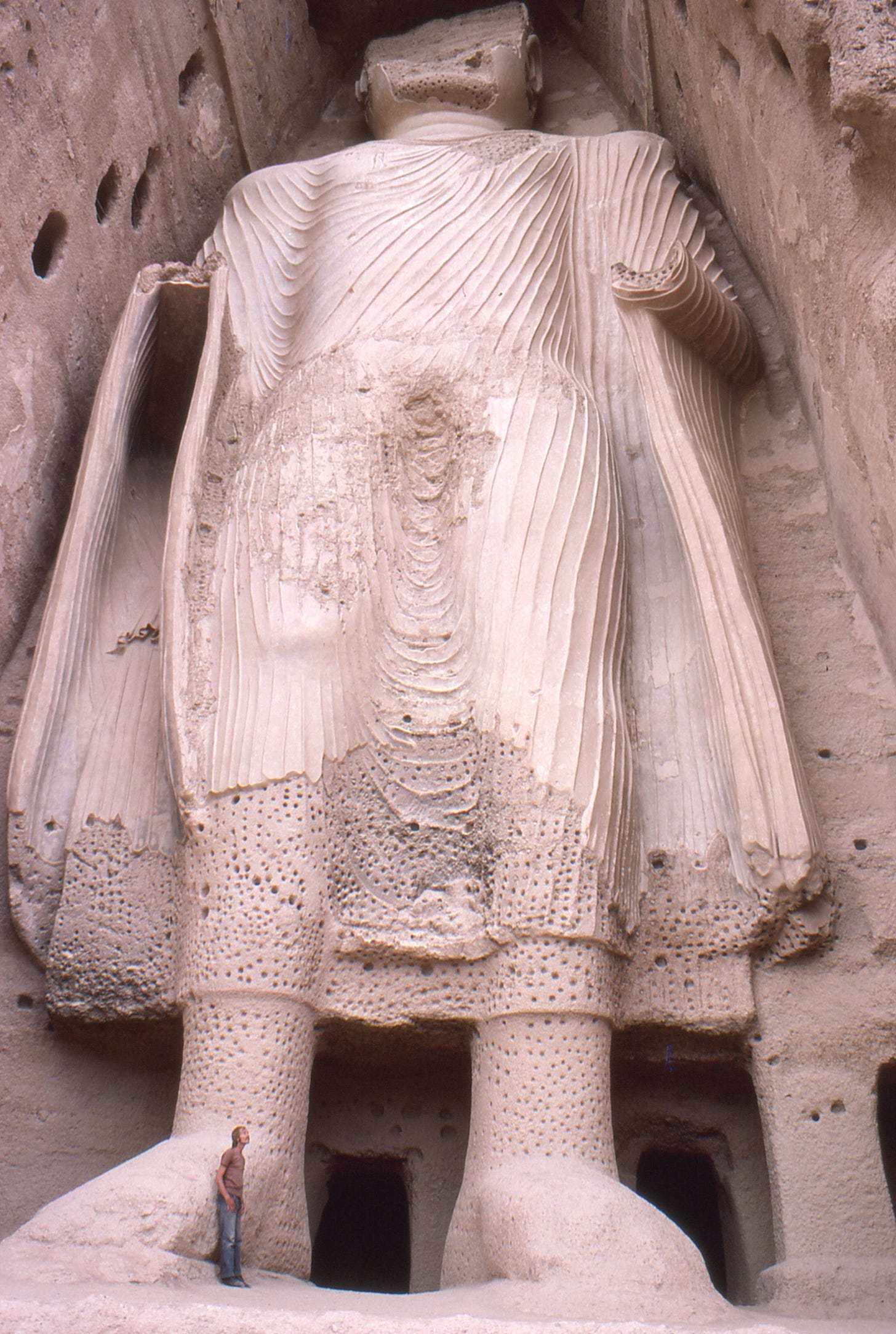

“Bamiyan is a beautiful, mountainous valley in Afghanistan,” he said, “where two giant Buddhas were carved into sandstone cliffs almost 1500 years ago. These Buddhas,” he added, “are the largest carvings of standing Buddhas in the world and some of most important cultural treasures in Afghanistan.”

Bamiyan sounded amazing to me, but it was not until October that I was able to see it in person. Several Peace Corps friends decided to travel there on a Sunday and invited me to go with them. Because of my job, however, I could not leave until the next day.

So I climbed on the bus alone Monday morning, with plans to meet my friends at the hotel in Bamiyan later that day. My memory is that the trip took about six hours, even though Bamiyan is only about 80 miles west of Kabul.

When I got on the bus, I sat next to the window. A woman in a chadri sat right in front of me, but all of the other passengers were men, and I was the only Westerner.

A man in his 30s, dressed in the usual long shirt and baggy pants, sat down on the seat next to me. His left hand was holding his swollen jaw, and he was clearly in great pain from an infected tooth. I’m not sure how he managed to cope as the bus started its slow, bumpy journey over the poorly maintained roads.

After about three hours, we stopped at a chaikhana (teahouse) in a little village. This allowed the passengers to stretch their legs, get some tea, and go to the bathroom. Unfortunately, “going to the bathroom” meant heading out into a treeless field. There were no bathrooms in the teahouse, not even an outhouse. This was easy enough for the men, but for me as a woman it was a bit difficult. I did the best I could to be inconspicuous, however.

Then I walked up to a vegetable seller and bought a potato that I asked the seller to cut in half. I had heard somewhere that a raw potato could help ease the pain of an infected tooth. (It probably has no effect at all, but I was trying to be helpful!) I handed the potato halves to my companion, who dutifully applied one to his throbbing tooth.

We climbed back on the bus and sat down in our seats again. That is when I noticed a pool of liquid on the seat and floor underneath the woman in the chadri. She must have been afraid to leave the bus, so she was forced to urinate on the seat. Her chadri gave her anonymity, but I felt so sorry for her—not the least because she had to sit in all that wetness for the next three hours.

Visiting the Buddhas

The bus eventually arrived in Bamiyan, and I met up with my friends at the hotel as planned. They eagerly told me all about the Buddhas, then walked me across a beautiful green valley so I could see them, too.

What can I say about the Buddhas? They were absolutely stunning.

The Buddha on the eastern side of the valley was carved about 570 CE, stood 38 meters (125 feet) tall, and was originally painted in a myriad of colors. The Buddha on the western side was carved about 618 CE, stood 55 meters (180 feet) tall, and was originally painted red.

I don’t know about you, but my brain doesn’t really comprehend measurements very well. What I can comprehend is that a grown person stood about as tall as the feet of the Buddhas!

Bamiyan was a Buddhist religious site from the 2nd century CE until the Muslim Turkic Ghaznavid dynasty conquered the area in 977 CE. During this time, the statues became a holy site for Buddhists travelling on the ancient Silk Road. Although the bodies of both Buddhas are carved into the cliff, their feet are freestanding. This allowed worshippers to make ritual walks around them.

A Chinese Buddhist pilgrim named Xuanzang visited Bamiyan in 630 CE. In the records of his journey, Da Tang Xiyu Ji, he wrote that Bamiyan was a flourishing Buddhist center with more than ten monasteries and more than a thousand monks. He also wrote that both Buddhas were decorated with gold and fine jewels.

In addition to the Buddhas, monks carved out caves in the surrounding cliffs as living spaces. Inside these caves—as well as on the ceilings and walls surrounding the Buddhas—they painted intricate murals.

By the time I visited the Buddhas, their colors had completely faded away, the gold and jewels were long gone, and their faces had been destroyed. What remained, however, were the magnificent bodies and the murals.

Scientists from around the world have analyzed the murals and found that the colors used to paint them contained pigments like vermilion and lead white. Binders for the pigments included natural resins and gums. According to Roger Highfield, 2008, murals in twelve out of 50 caves used paints based of oil, most likely derived from walnuts or poppies. This means the oil paintings in Bamiyan predate the invention of oil painting in Europe by as many as six centuries!

The Hazaras

Bamiyan is in the heart of Hazaristan, the traditional homeland of the Hazara people in the central mountains of Afghanistan. The Hazaras are a Dari speaking people whose ancestors include a mixture of Iranians, Turks and Mongols. With a population of approximately 4,500,000, they make up the third largest ethnic group in Afghanistan. Sizable numbers of them also live in Iran and Pakistan.

Although the Hazaras did not build the Buddhas, these huge statues have been central to their identity for centuries. In Hazara tradition, the larger statue depicts a man named Salsal (meaning “the light shines through the universe”), and the smaller statue depicts a woman named Shahmama (meaning Queen Mother). The story goes that they are a star-crossed pair of lovers whose love for each other ended in their death. Ever since then, they have watched over Bamiyan Valley, eternally parted and frozen in stone.

Unfortunately, Hazaras are the most persecuted group of people in Afghanistan. After the Afghans and British signed a treaty ending the Second Anglo-Afghan War in 1880, Abdur Rahman Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan, decided to bring Hazaristan, Turkistan and Kafiristan under his iron fist. When the Hazaras rebelled, he instigated an ethnic cleansing program that lasted from 1888 to 1893. The result is that 60% of the entire Hazara population—men, women and children—were massacred. He also forced thousands of Hazaras into exile and enslaved others. He even ordered that the faces of their beloved Buddhas be destroyed.

This process of marginalization and discrimination continues into the present, with the result that Hazaras’ access to education, economic development and critical decision-making processes has been limited.

Why has there been such hatred for these people?

I am not an expert, and I definitely don’t understand all of the historical and cultural influences. But I think one contributing factor is that the majority of Hazaras are Shia Muslims in a country that is overwhelmingly Sunni.

Another factor is that Afghanistan encompasses numerous ethnic groups and tribes whose loyalty is to their own tribe first. The concept of a larger country called Afghanistan was foisted on them by the 19th century British and Russian powers who used Afghans—and individual tribal leaders—as pawns in their political games.

Tribal mentality arises from a natural human inclination to associate with groups that share culture, ethnicity and/or a religion in common. The upside to these affiliations is that they create a collective identity that leads to a sense of security and belonging.

The downside is that they can also create an "us versus them" mentality. Leaders reward, take care of and benefit their own families and tribes while seeking to marginalize people from other tribes. In Afghanistan, it is the Pashtuns who have the power. They form the largest ethnic majority (40%-50%), and all of the kings (for more than 200 years) and presidents have been Pashtun.

I think tribalism is one of the major things that has made Afghanistan almost ungovernable. It has also made it almost impossible for the country to come together as a modern nation of ethnically diverse people that uses its amazing resources for the good of all.

Return to Kabul

After visiting the Buddhas, my friends and I walked back through the valley to our hotel. The sun was hot, and I was thirsty. All I wanted to drink was water—not some artificially sweetened, chemical-laden concoction of a soda.

A beautiful stream ran through the valley next to the path we were on. After looking at it with longing for a while, I finally knelt down and drank some lovely, cool, refreshing water.

The next day, we all returned to Kabul. The morning after our return, I woke up with fever, diarrhea and vomiting—all at the same time. The Peace Corps nurse determined that I had both giardia (a tiny parasite that causes diarrhea) and salmonella (a bacteria that causes diarrhea, fever and stomach cramps)—gifts of the lovely water that I drank.

For the next two weeks, I was sicker than I have ever been before. Thanks to antibiotics, I eventually healed, life went on, and I never drank water out of a stream in Afghanistan again! (Or anywhere else, actually.)

My next blog post

My blog post next Sunday will focus on my meeting with my future husband and the major changes that begin to take place in my life as a result.

I also plan to publish two supplemental posts in the coming days. One is on the delicious food of Afghanistan. The other is an overview of Islam. I am by no means an expert in this regard, simply a lay person. But I think it is important for Westerners to know something about Islam in order to better understand what is happening all over the Middle East today, not to mention the various forces underlying Afghan history and culture. (What’s the difference between Shias and Sunnis and why does it matter, anyway?)

Recommendation

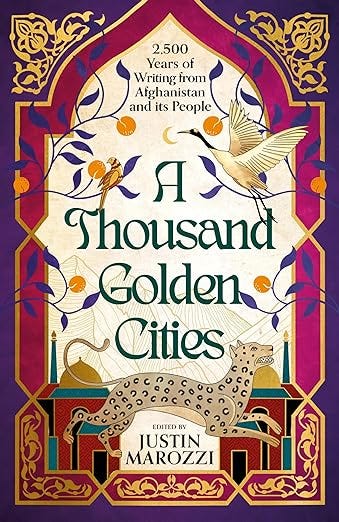

This wonderful book by English journalist, historian and travel writer Justin Marozzi was just published in November 2023. Within its 695 pages(!), you will find writings and poetry about Afghanistan—both by Afghans and by foreigners who have been mesmerized by the country over the centuries. The book begins with a passage from Herodotus (484-425 BCE), a Greek historian and geographer who was apparently the world’s first travel writer, and ends with modern-day Afghan poets writing both in Afghanistan and in exile.

It also includes a beautiful, poetic and heartbreaking Foreword by Masood Kahlili. Masood is an Afghan linguist, diplomat and poet, as well as the son of the beloved Afghan poet laureate, Ustad Khalilullah Khalili. The book just arrived yesterday, and I have only begun to read it. But I think I would have bought it in any case just to read this Foreword.

It is always nice to read something from people who stayed and got to know a place well rather than just passing through. I myself spent a couple weeks passing through Afghanistan in July 1975. As you have written, memories fade and while certain scenes are clear at hand others have faded completely.

I was lucky to carry a good camera in those days but the cost of film and possessing was a major part of my budget. Therefore I was lucky to average two pictures per day. In many instances my memories correspond to those photos but in other instances I have sharp memories about days when I never captured an image. (I have almost all my photos online at the Flickr website: https://www.flickr.com/search/?user_id=32267947%40N06&sort=relevance&view_all=1&tags=afghanistan ).

In those two weeks, I travelled by local bus from Pakistan to Kabul to Kandahar to Herat and then on to Iran. I travelled to Bamiyan and Bad-I-Amir and apparently stopped at that same roadside rest stop that you mentioned.

Strangely enough, I have not visited two countries that you know well. I have long wanted to visit Vienna (The Third Man is my fav old movie) and I have yet to see Ireland even though I am about 1/4 Irish ancestry. But I did manage to see and travel across Asia when it was possible and fun to do so.

Clarice, there is so much in this post. I kept reading and reading, enthralled by this pocket of the world that I know nothing about. The first picture is stunning, it reminds me a lot of Leh, Ladakh in India - I wonder if you've been there?

Funnily enough, the most memorable thing about this post for me was the poor lady on the bus - sometimes its the minutiae of travel that holds the most significance. That poor lady tells a whole story. I've just subscribed, absolutely stoked to read more of your explorations!